| Birds do it, beetles do it, maybe not educated

fleas, but certainly butterflies do it. That is, they use clever

structural engineering in their body parts to produce iridescent

colours without all the fuss of synthesising complex pigment

molecules. Physicists refer to the microscopic features on the

surface of a butterfly's wing, say, as photonic crystals.

Unlike pigments, which absorb or reflect certain frequencies of

light as a result of their chemical composition, photonic crystals

reflect light because of their surface characteristics. The crystal

array may reflect more blue light from one angle than another so the

fluttering of a butterfly or the dash of a kingfisher will produce a

beautiful array of colours.

Butterfly. Source: L. P. Biro et al., Physical Review

E, February 2003

Physicists would like to be able to emulate natural photonic

crystals for their own purposes but could also help biologists

better understand how different species make use of iridescence.

Now, Jean-Pol Vigneron of the University "Notre-Dame de la Paix"

in Namur, Belgium working with colleagues at the Research Institute

for Technical Physics and Materials Science, the Hungarian Natural

History Museum in Budapest and the Department of Applied and

Environmental Chemistry, at the University of Szeged, Hungary, have

discovered why the males in certain populations of lycaenid

butterflies carry a rather striking, photonic crystal colouration,

and males in other lycaenid populations do not. |

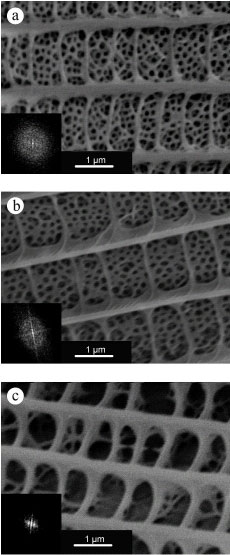

The researchers used high-resolution scanning

electron microscopy to take a close look at the wings of the

butterfly popularly known as Meleager's Blue (Meleageria

daphnis; but properly classified as Polyommatus

daphnis) and confirmed that the surface of the wings are coated

with tiny scales pitted with arrays of submicrometre-sized holes,

which form the structure of the natural photonic crystal, and give

the male wing a shimmery blue sheen.

Daphnis. Courtesy of photographer Mario Maier

The wings of the closely related butterfly from higher altitudes

(2000-2500m), the Persian Polyommatus marcidus, however,

lack these holes, and its wings are a dull brown. "The blue colour

can be attributed unambiguously to the fine, sponge-like medium,

called the "pepper-pot structure", present between the ridges and

the cross ribs in the scales of the coloured butterfly. Only traces

of this structure can be found on the scales of the discoloured

butterfly," explain the researchers.

The explanation lies in adaptation of each species to its

environment. At the warmer lower altitudes, the butterfly can afford

to be showy and, adds biologist Zsolt Balint of the Hungarian

Natural History Museum, "Even with their high reflectance they can

control overheating". But, its cousins eking out a living up the

mountain can get warmer in the sun by spreading their dull brown

wings to absorb previous heat. The researchers suggest that the

butterflies at high elevations trade flashy iridescence for

light-absorbing brown so that they can withstand colder temperatures

and garner enough energy during short sunny periods to survive long

enough to mate.

Female P daphnis. Courtesy of photographer Mario

Maier

This temperature effect might be put to good use in novel

clothing materials that have a photonic crystal coat allowing the

wearer to stay cooler in the desert by reflecting heat- inducing

light, but be switched for a non-iridescent form to help absorb heat

in the cold of space, for instance. |